Exclusive: An independent review of Amazon’s annual safety report finds that the company’s warehouse workers experience a disproportionate share of injuries.

Packages move down a conveyor system at an Amazon Fulfillment Center in Sacramento, California.

(Rich Pedroncelli / AP Photo)

In March 2024, Amazon released its annual safety report, announcing a decline in its warehouse injury rate for 2023. The company touted “meaningful, measurable progress” due to investments in new technologies, training programs, and safety personnel. When Irene Tung at the National Employment Law Project (NELP) looked at the underlying data, she saw a different story. “They can congratulate themselves on improvement from an injury rate that was beyond the pale to merely horrific,” she told me. “But it doesn’t mean that there’s no crisis there.”

A new report released by NELP and over a dozen other workers’ rights groups, based on recently released data from the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA), finds that Amazon workers experience a disproportionate share of injuries in the warehousing industry and that injuries at Amazon warehouses were more likely to be serious enough to require time off work. Amazon accounts for 79 percent of employment among warehouses with at least 1,000 workers, but 86 percent of all injuries. Last year, Amazon’s injury rate was more than one and a half times that of TJX (which owns T.J. Maxx, Marshalls, and other large retailers) and almost triple that of Walmart, the two comparable US warehouse employers.

That doesn’t surprise those working in the warehouse. Amazon has made same- or next-day delivery the core of its promise to customers, seemingly warping global supply chains to lightning speed for any and every product, from furniture to household supplies. Just this week, the company announced that it set new records for Prime delivery speeds in the first three months of 2024. The miraculously smooth customer experience is made possible by hundreds of thousands of warehouse workers, pushed to meet productivity quotas by a surveillance-based system of discipline.

“Amazon is well-known for its obsession with speed,” said G. Paul Blundell, who works at an Amazon delivery station outside Philadelphia. “Its intense digital tracking of employees is clearly designed to figure out how they can maximize the speed at which they get people to work. That speed is very much related to people getting injured because the vast majority of the injuries are repetitive stress injuries.” Keith Williams, a warehouse worker at the SWF1 warehouse in the Hudson Valley agreed. “They’ll always preach safety and taking your time, but then they’ll say, ‘This morning we need everyone to tackle the heavy stuff and get everything out as fast as possible.’” he said.

Williams is part of a coalition with other Amazon workers who have been pushing back against Amazon’s breakneck productivity goals, through organizing petitions in their workplaces and, now, calling for federal legislation. Today, Senator Ed Markey announced the introduction of the Warehouse Worker Protection Act, which would ban tracking by-the-second data like “time off task,” which measures the time between workers’ scans of items, and increase transparency around productivity quotas. It would also re-empower OSHA to create and enforce ergonomic work standards after decades of being prohibited from doing so without congressional authorization.

The OSHA report is based on the same self-reported injury rates that Amazon used in its in-house report. But according to NELP, the way Amazon framed its analysis was flawed. Amazon said that its injury rates, at 6.5 per 100 employees, were comparable to the average rate of warehouses with more than 1,000 employees. But since Amazon employs 79 percent of all workers in this sector, its own numbers have a disproportionate effect on that average. Using data from OSHA, NELP calculated what the average would be excluding Amazon. For non-Amazon warehouses with over 1,000 employees, the injury rate was 3.8 per 100 employees, making Amazon’s overall injury rate 71 percent higher than its peers’. (Amazon did not provide a statement on NELP’s analysis by the time of publication and referred back to its original report.)

Current Issue

In its report, Amazon highlights improvements in its “lost time” rate, referring to injuries that require missed days of work. But the report does not address another related rate: the “light duty” rate, or the rate of injuries that require a job transfer. Amazon is required to report “light duty” injuries to OSHA, and NELP found that the company’s “light duty” rate was 5.1 per 100 employees, almost double the national average for warehousing overall. That gap is even bigger when comparing Amazon’s “light duty” injury rate to the industry average excluding Amazon, which is just 1.6. A 2023 report by the Strategic Organizing Center found that Amazon may even be shifting cases that should have been classified as “lost time” to “light duty” to save money on workers’ compensation cases.

In August of 2023, Williams was working in a trailer alone when a stack of boxes fell, and a 45-pound box containing a computer desk hit the base of his neck. He was told he wouldn’t be able to recover at home and was instead directed to complete administrative tasks on a computer. After two and a half months of light duty, Williams returned to standard work, but quickly started to feel weakness in his wrists and elbows. “It got so bad that I couldn’t lift a one-pound box,” he said. His doctor told him that he had never fully recovered from the initial incident, which had caused a pinched nerve. Blundell said he knew many workers who had to use their personal leave for recovery time because the company didn’t grant it.

The most common injuries at Amazon are ergonomic—“strain, sprain, and pain.” In its report, Amazon touted ergonomic improvements made in 2023, but did not mention that many of these improvements were mandated by OSHA, which has cited Amazon for safety hazards resulting from prioritizing speed over safety. Before coming to Amazon, Blundell had worked on a farm and in construction. Within four months of working at Amazon, he had a rotator cuff injury in both shoulders and couldn’t lift his arms without sharp pain. Managers had assigned him to the same task every day since he started the job four months prior—stowing, one of the most physically rigorous tasks—because their rate tracking showed he was good at it. When he reported his injury, the regional safety manager who was visiting the building that day attributed it to his past work in construction, though by that time, Blundell hadn’t worked construction for a year.

Both the NELP analysis and Amazon workers point to the company’s surveillance-based pressure to make work rates as a key cause of injuries. Workers are more likely to strain themselves under an automatic discipline system based on continual monitoring of their work. Amazon managers dole out write-ups based on “time off task,” the number of seconds between a worker’s scans, including when they’re in the bathroom or addressing issues like a machine malfunction or damaged box. Williams said managers push workers to hurry back from their 15-minute breaks early to minimize their time between scans. Managers also try to incentivize workers to work faster through competitions for “swag bucks,” which allow workers to purchase company merch.

Amazon has denied using these quotas to discipline or fire workers. A company spokesperson recently stated, “We do not require employees to meet specific productivity speeds or targets.” But internal company documents obtained through FOIA by The Verge in 2019 described how the company disciplined and terminated workers based on algorithmically generated quotas. A signed letter from an attorney representing Amazon detailed how the company fired “hundreds” of employees at just one Baltimore warehouse for failing to meet productivity quotas between August 2017 and September 2018. The letter also said that Amazon’s tracking system “automatically” generates warnings or terminations based on productivity without requiring supervisor input.

Since both the OSHA data and Amazon’s report are based on the company’s mandated self-reporting of injury rates, advocates say those numbers likely undercount the full scope of the issue. OSHA mandates that companies report injuries that “require medical attention,” but in practice, NELP’s Irene Tung says, only “very serious” injuries make it across the threshold of being reported. Ninety-five percent of Amazon’s reported injuries are those that require missed days of work or a job transfer. “That might speak to how many are not being recorded, if basically all the ones being reported are the ones where a person cannot physically do the job anymore,” Tung said. Williams said that Amazon’s in-house medical team, AmCare, made him feel pressured not to report his injury. “They’ll say ‘We can give you aspirin and you can wait here for 15 minutes, but if you say it’s still hurting you, we have to get your manager involved,’” he said. “‘It’s like, ‘we have to let your manager know that you’re not performing well.’”

Popular

“swipe left below to view more authors”Swipe →

These safety issues have become a rallying point for workers at Williams’s warehouse and others pushing for more sustainable, safer working conditions. Last month, an organizing committee of workers at Williams’s warehouse delivered a petition to management asking for access to their own productivity rate data and transparency about the standards being used to discipline workers. He says management has responded by trying to have one-on-one conversations with workers, rather than respond to the organized group and its demands.

At his warehouse outside of Philadelphia, Blundell has been organizing with the group Amazonians United to improve working conditions and win dignity and control on the shop floor. The speed of work has been a central organizing focus, particularly the chronic under-staffing that leads managers to rely on fewer workers to complete a larger workload. “Managers would make sure the front of the belt was fully staffed with the strongest, fastest workers,” says Blundell. “And they’d push them to work really fast all day long. And then they’d understaff the rest of the building, which meant these packages come flying down the belt and pile up.”

Blundell and his coworkers drafted a petition with demands that included appropriate staffing on the belt, as well as the right to hit the emergency stop button on the belt in cases where the resulting package spillover would constitute an OSHA violation. Seventy-five percent of the warehouse signed on to the petition, which led to management increasing staffing, and allowing the use of the emergency stop button in unsafe situations. “Management had made it our problem before—their unsafe behavior,” he said. “By organizing each other, we were able to make their unsafe behavior their problem.”

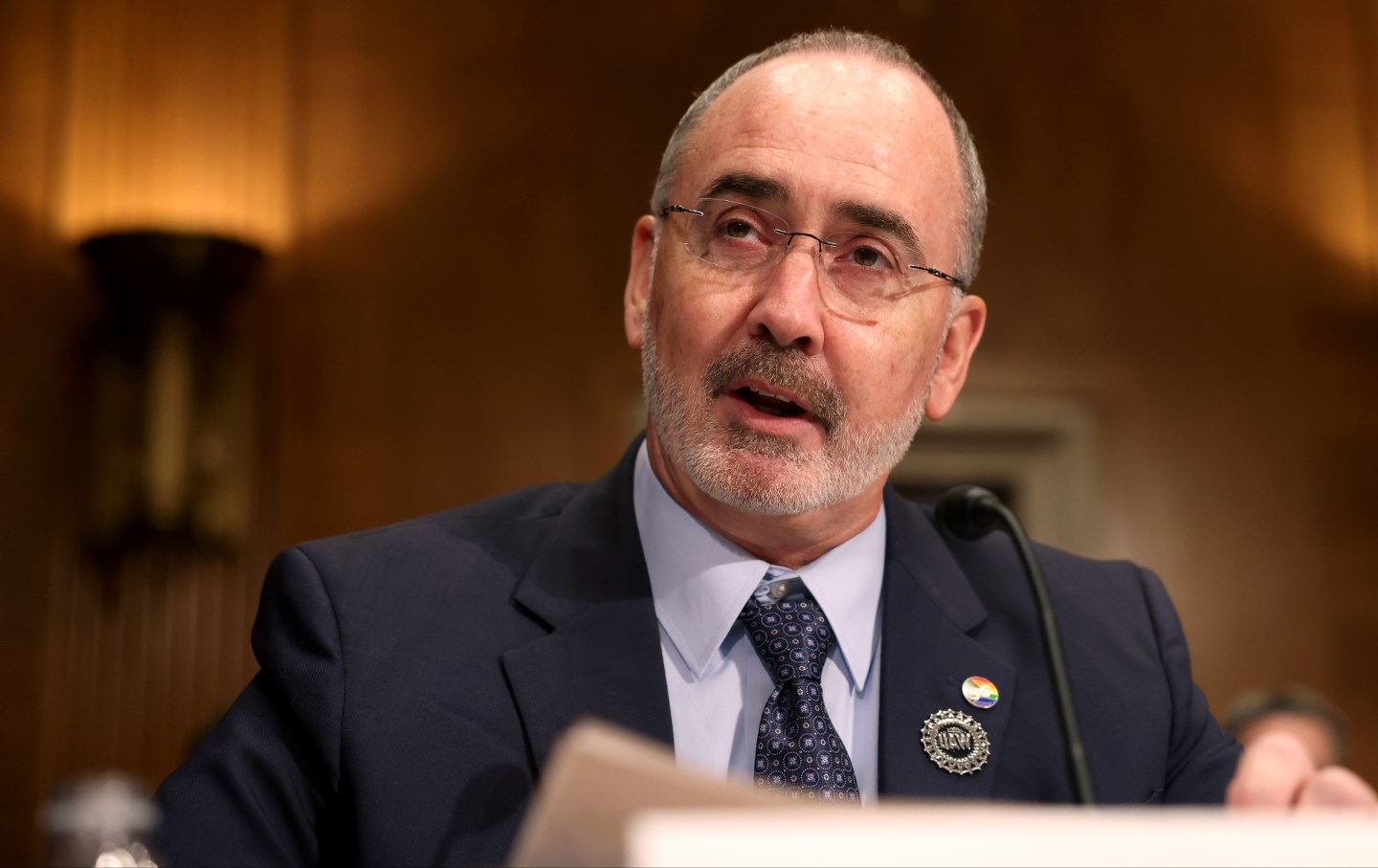

The pre-Amazon warehousing and logistics industry offered middle-income, stable jobs, especially in unionized workplaces. “That’s a far cry from the jobs we see at Amazon now,” said Tung, where safety risks contribute to high employee turnover rates. As workers push for improvements in safety standards on the shop floor, the Warehouse Worker Protection Act aims to fill in the gaps in labor law that companies like Amazon have exploited to fuel their growth. Today, Sen. Ed Markey and Teamsters President Sean O’Brien announced the introduction of the new federal bill, which would ban tracking practices like “time off task” and the process of using quotas to rank workers against each other.

Williams and other warehouse workers are advocating for the bill, which would also establish transparency requirements for automated discipline, give warehouse workers the right to request and review their work speed data, and protect workers from retaliation for requesting this information. The legislation’s enforcement mechanisms include a private right of action for workers over violations, authorizing the Department of Labor to impose civil penalties for violations, and strengthening OSHA’s enforcement authority by making it more difficult for employers to delay correcting violations. The federal legislation builds on recently passed laws in California, New York, Minnesota, and Washington and is being supported by a broad alliance of unions including the Teamsters, worker centers, and advocacy groups including NELP and the Athena Coalition.

“The Warehouse Worker Protection Act is about dignity, safety, and respect for the workers that make companies run,” Senator Markey told The Nation. “When corporations repeatedly use and abuse warehouse workers, they show us that their number one obligation is to their profits. This bill would guarantee that we have basic standards in place to protect warehouse workers from the worst of corporate greed and move us one step further towards true worker justice.”

The legislation would also direct OSHA to create an ergonomics standard, which it has been prohibited from doing for more than 20 years. The agency passed an ergonomics standard in 2000, but after pushback from industry groups President Bush signed a bill repealing the rule and prohibiting OSHA from issuing another without being explicitly asked to do so by Congress.

Since then, Amazon’s rising goliath status created a race to the bottom for safety standards. “All other companies have their eyes on Amazon,” Tung said. “Because you have to be able to compete with Amazon if you’re going to survive.” Improving conditions at Amazon, the second-largest private-sector employer in the country, could have industry-wide implications. Currently, there are no federal protections for workers from discipline based on productivity rates.“What’s happening at Amazon is really a symptom of the fact that the worker protections we have on the books have really not kept pace with new technologies in the workplace and were really inadequate to begin with,” Tung said.

In the meantime, Williams and his coworkers are continuing to organize on the shop floor, and he hopes the federal legislation will support their efforts. “We’re just going to keep on the pressure until change actually happens,” said Williams. “We know what their response is always going to be. We want the response to be change.”

Thank you for reading The Nation!

We hope you enjoyed the story you just read, just one of the many incisive, deeply-reported articles we publish daily. Now more than ever, we need fearless journalism that shifts the needle on important issues, uncovers malfeasance and corruption, and uplifts voices and perspectives that often go unheard in mainstream media.

Throughout this critical election year and a time of media austerity and renewed campus activism and rising labor organizing, independent journalism that gets to the heart of the matter is more critical than ever before. Donate right now and help us hold the powerful accountable, shine a light on issues that would otherwise be swept under the rug, and build a more just and equitable future.

For nearly 160 years, The Nation has stood for truth, justice, and moral clarity. As a reader-supported publication, we are not beholden to the whims of advertisers or a corporate owner. But it does take financial resources to report on stories that may take weeks or months to properly investigate, thoroughly edit and fact-check articles, and get our stories into the hands of readers.

Donate today and stand with us for a better future. Thank you for being a supporter of independent journalism.

Thank you for your generosity.

More from The Nation

Will California’s new farmworker labor law survive this assault by the not-so-wonderful Wonderful Company?

David Bacon

The problem is systemic: Freelance life is underpaid. The solution must be systemic too.

Amy Littlefield

The Labor Notes conference explodes, with growing ranks of unionists, new organizers taking on goliaths like Amazon and Starbucks, and veterans invigorated by reform victories.

Ella Fanger

Human Rights Watch just let go of 39 staffers. Workers are demanding executives take pay cuts instead

Highlights

/

Saliha Bayrak

“These companies are more profitable than the Big Three ever dreamed of being, and the workers are paid even less.”

Q&A

/

John Nichols

The former crypto mogul faces a 25-year sentence for his financial con game

Jacob Silverman