May 9, 2024

With Grants Pass, the Supreme Court appears set to allow cities, counties, and states to criminalize homelessness.

On a sunny, cold February day, I drove four hours from Portland, Oregon, to Grants Pass, a town of about 40,000 in the southern part of the state. I wanted to talk to residents about the homelessness crisis there and ask whether they thought the city should still be allowed to punish its roughly 600 unhoused people for not having a home.

Grants Pass has no operating emergency shelter. Yet a few years ago, it passed a number of anti-sleeping laws that made it impossible for people in the city without homes to avoid constant fines and jail time. Then, in 2022, the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals issued a permanent injunction to bar the enforcement of such anti-homelessness provisions.

I headed to Morrison Park, where four people sat around a picnic table next to a pair of tents and a pickleball court. After I pulled into the parking lot of a carpet store across the street, a man came out to talk to me. He was angry about the people in the park, telling me that it was ridiculous that “people”—meaning people with homes—could no longer use their public spaces. He wanted to punish the homeless. Liberal policies, he said, had created chaos in deep-red southern Oregon.

Current Issue

Donald Trump won Josephine County, where Grants Pass is located, by 26 points in 2020, but Republicans are not alone in their antipathy toward the unhoused. The failure to generate affordable and supportive housing is bipartisan and widespread.

Between 2021 and 2022, the number of people experiencing homelessness increased in 41 states. Western states reported especially high rates. Between 2020 and 2022, Oregon saw a 22.5 percent spike in homelessness.

Two months later, I was on the other side of the country, at the Supreme Court, to hear the oral arguments in Grants Pass v. Johnson, a case that will determine whether city ordinances that impose civil or criminal penalties for involuntary homelessness constitute cruel and unusual punishment.

The case made its way to the Supreme Court largely because the Grants Pass ordinances were especially harsh. In addition to banning the use of bedding materials “for the purpose of maintaining a temporary place to live,” the city would sometimes shut off the water and close public restrooms in the parks. Helen Cruz, who has lived in Grants Pass since she was 4 and has been intermittently homeless, told me the ordinances were intended to make life uncomfortable enough that people would leave. “One cop even asked me, ‘Well, why don’t you just move?’” she recalled.

Liberal cities in the Ninth Circuit, such as San Francisco and Los Angeles, filed amicus briefs supporting neither party, and district attorneys from San Diego, Sacramento, and other blue cities joined Idaho, Montana, and 22 other states that support the city of Grants Pass and claim that the Ninth Circuit’s injunction removes the punitive tools needed to solve local homelessness issues.

The justices spent the two and a half hours of oral arguments discussing where the line should be drawn between the status of being homeless and the conduct associated with it. The status precedent comes from a 1962 case, Robinson v. California, which determined that a person cannot be punished simply for being addicted to narcotics. The justices ruled that the Eighth Amendment prohibits the state from punishing an act or condition if it is the unavoidable consequence of one’s status or being.

Ticketing people for having nowhere to go penalizes them for not being able to overcome skyrocketing rents, low wages, and a lack of healthcare. If the court—as seems likely—rules that cities, counties, and states can criminalize sleeping outdoors, this crisis will get worse. Laws likes the ones in Grants Pass will push unhoused residents further into poverty, harming their mental health and potentially leading to substance-use disorders.

Ask any case worker about homelessness, and they will list the barriers their clients face in obtaining housing: prior evictions, criminal records, and the inaccessibility of healthcare. Note that “lack of jail time” and “too little debt” are not on the list.

Even right-wing Justices Brett Kavanaugh and Amy Coney Barrett asked the counsel for Grants Pass where homeless people are expected to go after serving a jail sentence. The lawyer said that the jail would hypothetically connect people to services, but she had no good answer for what happens when housing and services are not available.

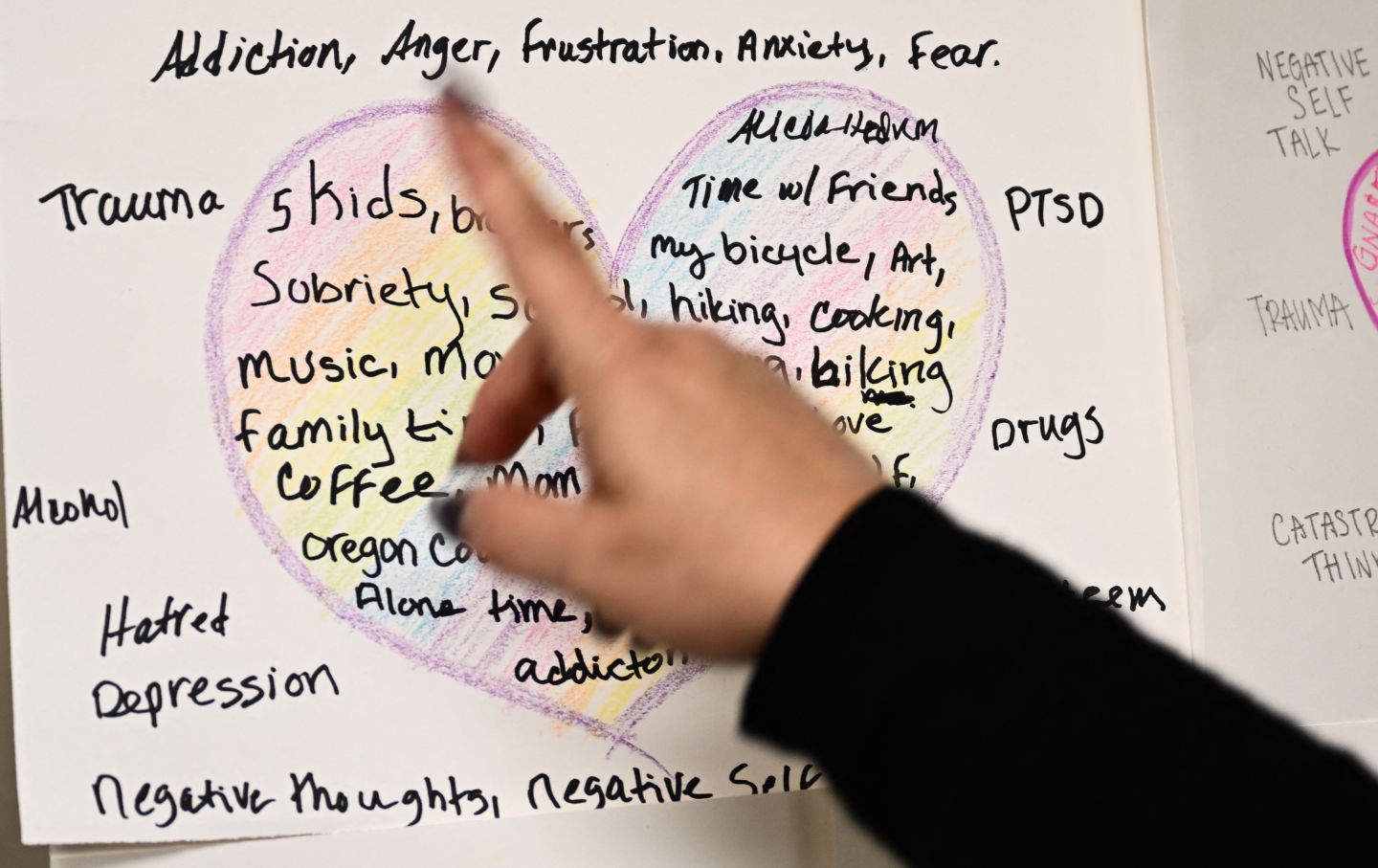

As in other places, people with disabilities, people of color, and LGBTQ individuals are disproportionately represented in the homelessness statistics for Grants Pass. All the homeless residents I spoke with had experienced trauma. We know what helps homelessness: affordable housing and healthcare.

Back in February, Helen Cruz told me there was a third thing that could help—something the Supreme Court could make more difficult. “People out here, they’ve got nothing to lose and nothing to look forward to,” Cruz said. “Just give them a little bit of hope, because a lot of them out there have none.”

Thank you for reading The Nation!

We hope you enjoyed the story you just read, just one of the many incisive, deeply-reported articles we publish daily. Now more than ever, we need fearless journalism that shifts the needle on important issues, uncovers malfeasance and corruption, and uplifts voices and perspectives that often go unheard in mainstream media.

Throughout this critical election year and a time of media austerity and renewed campus activism and rising labor organizing, independent journalism that gets to the heart of the matter is more critical than ever before. Donate right now and help us hold the powerful accountable, shine a light on issues that would otherwise be swept under the rug, and build a more just and equitable future.

For nearly 160 years, The Nation has stood for truth, justice, and moral clarity. As a reader-supported publication, we are not beholden to the whims of advertisers or a corporate owner. But it does take financial resources to report on stories that may take weeks or months to properly investigate, thoroughly edit and fact-check articles, and get our stories into the hands of readers.

Donate today and stand with us for a better future. Thank you for being a supporter of independent journalism.

Thank you for your generosity.

More from The Nation

The potential next president and his allies are looking at the campus-led crackdown on free speech as a perfect dress rehearsal.

Gregg Gonsalves

The state’s landmark decriminalization initiative wasn’t given a real chance.

Comment

/

Lydia Kiesling

While the mainstream media repeatedly mischaracterizes pro-Palestine protests on campus, police and university administrations are attempting to repress the student press.

StudentNation

/

Amber X. Chen

![]()

The industry-friendly skies… Cuba libre… Bosses are getting the boot, too…

Letters

/

Our Readers

Columbia has tossed aside the mission at the heart of undergraduate liberal arts education: preparing student to be citizens in a pluralistic democracy.

Joseph A. Howley

Restrictive laws don’t just take away the right to choose, say physicians and ob-gyns, but also prevent proper treatment of pregnancies.

Column

/

Katha Pollitt