Liberal originalists’ most important contribution is the insight they share with Ponnuru and his conservative allies: that constitutional interpretation is not just for judges and lawyers in lawsuits but rather forged in what Amar has called a “constitutional conversation” and others have labeled “popular constitutionalism.” Balkin starts a 1998 law review article, co-authored with University of Texas’s Sanford Levinson, with Frederick Douglass’s famous 1860 speech in Glasgow, Scotland, rebutting Dred Scott v. Sandford, the U.S. Supreme Court’s noxious ruling that the Constitution barred African American individuals from citizenship or “any rights that a white men is bound to respect.” In that speech, Douglass advanced what he called a “strict constructionist” argument that “only the text,” not the subjective expectations of drafters or ratifiers, or “commentaries” or judges “who wished to give the text a meaning apart from its plain reading, was adopted as the Constitution of the United States.” Nowhere in the document did the word “slavery” appear, Douglass noted, “nor any provisions preventing Congress or individual states from abolishing slavery.” Just as Douglass’s antislavery reading of the Constitution eventually became the law of the land, Balkin and Levinson stressed that transformational constitutional changes typically start with well-designed political and social movements that articulate new interpretations and move them from “off the wall” to “on the wall,” well before they are blessed by the Supreme Court.

Unlike Douglass, contemporary liberal leaders largely have not recognized that, in our democratic polity, battles over the meaning of the Constitution are inherently political, and must be waged as such. To correct that ahistorical misperception, liberals must shed a related habit: the visceral antagonism to the label “originalism.” Berkeley Law dean and star litigator Erwin Chemerinsky, with whom I rarely disagree and whom I hugely admire, published a book in 2022 whose title, Worse Than Nothing: The Dangerous Fallacy of Originalism, unwittingly reinforces Ponnuru’s false claim that liberals have “nothing”—no strategy, no theory to counter conservatives’ originalism. They do, as I’ve demonstrated above, but liberal leaders have largely failed to engage with conservatives’ originalist sloganeering.

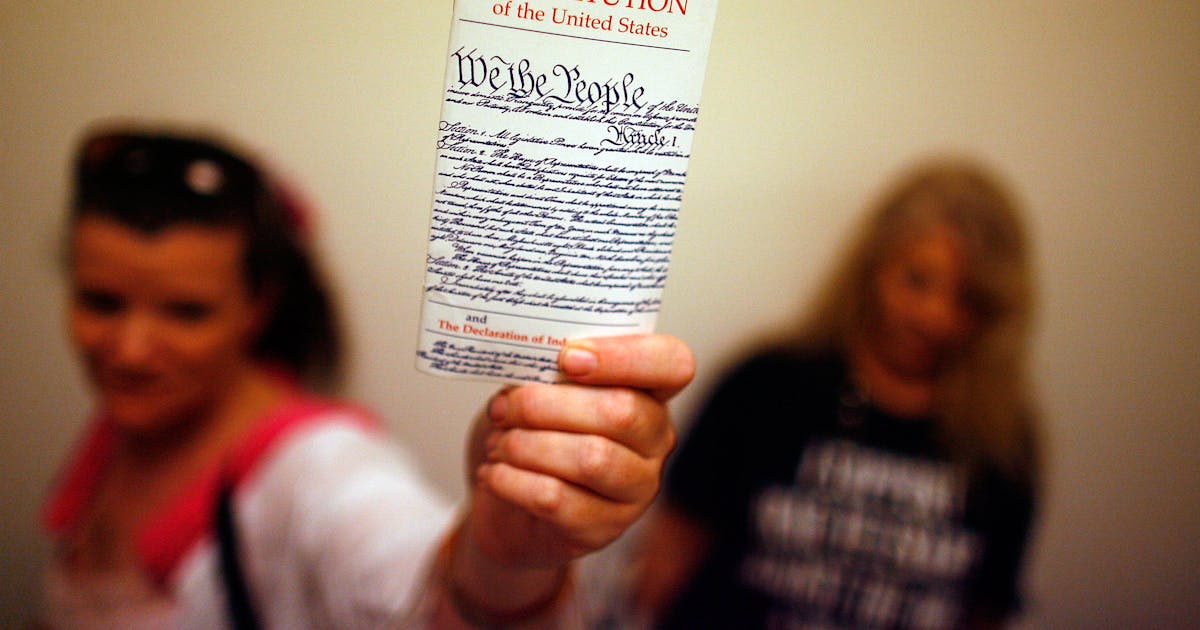

The label “originalism” itself does not, of course, galvanize broad swaths of everyday Americans; most do not know or care what it means, if they have heard it at all. But conservatives’ endless professions of fealty to originalism, together with liberals’ long-standing scorn or indifferent silence, has led to widespread credence that conservatives take seriously the actual words of the Constitution and what the Framers had in mind when they wrote or ratified them, and liberals … well, not so much. Given Americans’ veneration of the Constitution as secular scripture and their regard for the rule of law, such perceptions, left unanswered, damage liberal prospects in the wars over the Constitution and the courts.